Hey Person!

Here are the nine stages of rage / action / acceptance when it comes to dealing with someone ripping off your work:

1. Fury

2. Angry Tweeting

3. Regrets over angry tweeting and people calling you a troll

4. Writing the person directly in a way that is gentle, respectful, and educational

5. Receiving a defensive angry email back

6. Having your rep send an official stern letter

7a. They take the project down / send some form of apology (if it's an individual)

7b. They force you to file an official complaint with their legal team (if it's a company)

8. Feeling awful / exhausted no matter what happens

9. Pastries

(I recommend skipping the first three steps if you can)

The truth is, it’s pretty tough to get someone to acknowledge / offer compensation for a style ripoff. If you’re talking about someone working in your same medium or someone who was obviously the cheap version of you at the time of hire, chances are any pursuing / letter-writing you do will not lead to financial compensation. The best thing you can do is try to educate the person that ripped you off—they’re likely young and just don't know any better. If you do it in a way that is kind, you might end up making an ally instead of an enemy and they'll tread more carefully on future projects.

I used to get people sending me style rip-off-ers all the time, but they’ve definitely started to taper off. I think the style of lettering I helped to develop/revitalize just became so popular that people think of it as public domain now. I don’t mind, as the work is still coming in steadily and most of the people that are way too close to me stylistically acknowledge in some way that I was/am a big influence on their work. I try not to carry animosity toward the ones who don’t because that kind of stress makes you die young. The best medicine is to just keep working and know that any time and energy you spend getting panicky rage over people ripping you off takes away from your ability to make work. When you’re first starting out, you’re so defensive about your position in the industry because all the good stuff just started happening, but if you can keep the ball rolling and keep making awesome work, what once was a soul-crushing fury will turn into a barely noticeable annoyance that can at times legitimately feel flattering.

If you’re talking about someone ACTUALLY ripping off your work (i.e. reusing an image of yours without your permission or copying an image of yours exactly), there are of course ways to get compensation for the infringement but once you start threatening anything legal, especially with a bigger company, they will bury you in paperwork. Usually large companies have an in-house legal team that can devote endless hours to writing hard to read letters saying that what they have done is perfectly legal. Your lawyer must respond, and in no time the legal fees you're paying to keep up with the paperwork volleying start doubling / tripling / quintupling whatever the original fee might have been for the project had they hired you. I wouldn’t ignore a true rip-off, definitely send a letter to the artist (a much more stern one than you would to a style rip-off, but still give them the benefit of the doubt that they’re probably young and made a mistake and are not an awful human). Hopefully you'll get an apology back. The company, on the other hand, will be less likely to acknowledge / apologize without a fight.

There are brave souls that take on large companies when rip-offs happen (like Modern Dog) but if you followed their journey (which thankfully had a happy ending) it was full of heartache and stress, they had to sell their studio to pay legal fees, etc. If you’ve got the balls, the time, and the money to do it, and the company is CLEARLY doing something illegal by reusing / tracing your work, fight. Your battle will be tough, but you'll find plenty of support in the community for it.

The best advice I can give you is to copyright your images so that if a clear cut case of stealing comes across your plate, you have some ground to stand on legally. While you of course “own the copyright” to the images you create unless you're transferring them to the client in a contract, it’s difficult to pursue copyright infringement cases without having filed for copyright of the images officially.

Hopefully that helps!

J

Note: What follows is email correspondence between myself and a designer seeking advice. Names have been anonymousized, and I’ve subtracted praise since it would be icky of me to just post praisey emails.

Dear Ms. Hische,

My name is Person, I’m 21 and I’m going to be graduating from college in the spring with a degree in Graphic Design. I love doing lettering and illustration, especially chalk board signage and stuff like that, and I think that in the future I’ll be happiest doing freelance work on my own. But right now I have a job lined up for after I graduate at a giant company doing UX stuff (which I kind of hate) but this is the kind of deal where I can get a good salary and health insurance and stuff that I honestly could really use. I always figured I could just do freelance on the side until I can make it doing just that.

But one of my teachers just told us that the first few jobs we take after we graduate will dictate the work we do for the rest of our lives, because that will decide what our portfolios looks like. After class I went home and immediately burst into tears. I don’t want to be in a cubicle forever, I hate this job! I feel like I’m wasting valuable post-graduation time, but I need a roof over my head too.

Should I listen to my teacher and ditch this job and start hunting around for an internship at a studio that might not pay as well? Can I start making a name for myself doing freelance now? How did you go about making your promo to start freelancing? How can I take what I love and make it into a living like you did, what steps should I take?

I’m so sorry this is so long, but I really can’t thank you enough for reading through it.

Sincerely,

Person McPerson

Hey Person!

What your professor said is partially true, but it’s also a very very high pressure statement. It’s true that every job you have will affect your portfolio if you let it, but you could be a lion tamer during the day as long as you found time to do design at night. There’s no reason why you need to include the work from a crappy job in your portfolio if you’re finding time to make good work on your own. Professors say things like this because 90% of design students don’t have the motivation to go home after their day job and make a cool promo, or work on freelance work. They need their job to be what fuels their portfolio because they have a hard time doing it on their own.

What your professor said puts way too much pressure on you to get an amazing job straight out of school—which is REALLY REALLY hard! You’re young, take whatever job you think you will learn learn the most from and even if it’s not a “dream job”, there’s plenty to learn. Even cubicle jobs teach you a lot about how to deal with different kinds of personality types in office environments, how to write respectful emails, etc. Also, some people need to take higher paying less fun jobs when they’re young because of their life situation. Some people need amazing health insurance because of health issues, some people need a high salary because they’re supporting a parent or small child. The key is to take a job that doesn’t make you hate design and supports your development as a designer in one way or another, even if it’s just sugar-daddying your night time passion projects.

Internships are incredibly valuable and yes they pay very little. Tiny design studios pay lower salaries as well but you will learn a great deal by working at them. When I started out, I went the tiny studio route because I was fine living like a broke college student until my mid-twenties and because my day job also had 9-6 hours (instead of 9am-10pm hours that you often see at small creative agencies), which enabled me to freelance at night and eventually go on my own.

Do what feels right to you. If having a stable income takes a giant load off of your shoulders and allows you to be creative at night, keep that stable income job, but if it’s making you hate design and you come home exhausted and unable to work on your own stuff, quit it for sure.

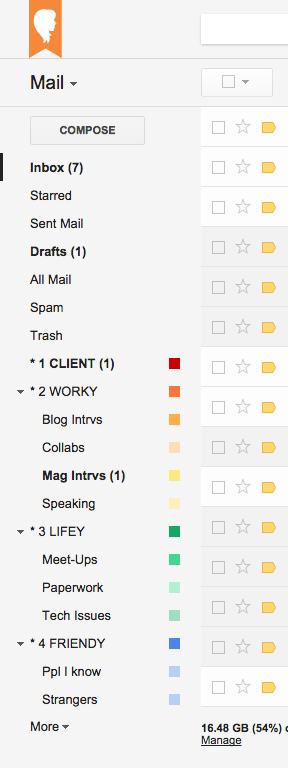

As far as when to go freelance: I’d recommend having 3-6 months of rent / living costs in the bank before you do since it can take a while for the ball to really get rolling. I was working full time and freelancing “full time” (6-8 hours after work) for over a year before I quit my day job. I had enough saved that I didn’t suffocate under the pressure to make money in my first few months out.

Hopefully this helps!

J

Note: What follows is email correspondence between myself and a designer seeking advice. Names have been anonymousized, and I’ve subtracted praise since it would be icky of me to just post praisey emails.

Hi Jessica,

I recently graduated from a graphic and package design program (whoop!) and I’m really struggling with applying all that I’ve learned to “the real world.” I interned at a fairly large branding and design company for six months and found myself drowning. While everyone there said I kicked ass as an intern, I really didn’t feel like I was getting the direction that I needed; it was literally sink or swim. Not getting proper direction made me feel lost, and eventually I started questioning my abilities as a designer. Since I’ve left, I been trying to pick up the pieces to regain that go-get-’em confidence I once had.

This leads me to the reason I’m writing you. In the way you tell your story, it seems so divine; the way you seamlessly moved from one place to another and eventually found your way to doing it all on your own. Was there ever a time when you had overwhelming doubts about where you were going in your career, and questioned whether you were competent enough to pursue all you dreams? I know these are incredibly intimate questions, and feel free not to answer them, but being an over-sharer, I had hoped you wouldn’t mind. Any advice would be very much appreciated.

Thank you,

Person McPerson

Hey Person!

There are definitely times even now when I question the decisions I make about my career. Doubt and anxiety are totally normal and happen no matter how much success you have. You’re in a good place already if you can see what is missing from your life / your career, the only thing to do next is to come up with solutions of how to get that missing piece back in your life. If what you’re missing is direct interaction with a mentor or someone whose opinion you trust, there are a few ways around this. You could reach out to any designer in your area and see if you can buy them lunch in exchange for a portfolio review or see if they would be game for on-going critiques. I find that critiques from peers can also satisfy a good deal of this since so often the problem for me is really just showing the work to ANYONE before I send it to the client. It could even be a non-designer—having to explain my process to them, and having to talk about my work lets me see holes in the concepts and areas that can be improved upon.

Questioning your abilities is far better than blindly moving forward thinking you’re awesome and never stepping back to question the work that you’re doing. Just judge yourself against yourself, not against people you feel are leagues away from you. Have you improved over the last year? If not, what do you think held you back. If you have improved, what do you think helped most to move your work forward and what can you do to continue improving? It can be super intimidating if you’re always comparing yourself to other people, especially other people that for one reason or another have had more time to practice or more opportunities to learn under a mentor. I’m sure you learned a ton at the big branding place that you worked though maybe it was more about how you want to run a business in the future and what kind of job environment is best for you.

I have to step back constantly and look at the things that are good in my career and the things that I feel like I’m missing or can improve upon. Half of my side projects started because there was a skill I wanted to practice or something that I was excited to make but no one was hiring me to make it. Now at this point in my career, I’m torn between wanting to write and educate more since I love to help people like yourself find their way or feel less intimidated to start projects, but I get very depressed when I spend too much time talking about work and not enough time actually making it. I stretch myself too thin and feel like I don’t devote enough time to client projects. There is always something that you’ll be frustrated by or overwhelmed with in your career, just find a way to step back, look at what’s bothering you, and see what steps you can take to fix it, even if they’re small and gradual.

All the best,

J

Note: This text was created as a talk for An Event Apart in San Diego. It was presented Tuesday, May 21st 2013. Many thanks to Stephen Coles for his advising and light editing. While the full slide deck is not shown below, about a quarter of the original slides are used as editorial illustrations. To send comments or propose corrections (kind and helpful tone appreciated), email me.

Type Designers are your new best friends.

If you are a web designer, you are used to tedium. You are used to spending entirely too much time hovering over a keyboard googling endless combinations of words to figure out why something looks beautiful in Chrome but like a flaming pile of poo in Firefox. You write your own CSS and after the project is done you comb through it all to make it “prettier”. You can’t handle how some people format their PHP. You are a unique and wonderful kind of human—someone intensely focused on details that most people will never ever notice. You say to yourself “I don’t care that no one will ever appreciate this backbreaking work I’m doing except other intensely nerdy people like me. I care, the nerds care, and that’s enough for me.” If you are thinking to yourself “Wow! It’s uncanny how much this describes me!” You are awesome. You make the internet a better place. Take a deep breath and bask in your own awesomeness.

I want to introduce you to your brother from another mother—another group of humans that, like you, is quite under-appreciated: the type designer. Type designers and web designers have an amazing amount in common, that’s why it’s super wonderful that they’ve been collaborating more lately. Web designers are pumped that they can use more than a handful of fonts on the internet, and type designers are pumped that this new group of people using their fonts actually know how to use computers. You would be shocked at how many people try to download .zip files onto their iPhone to install fonts.

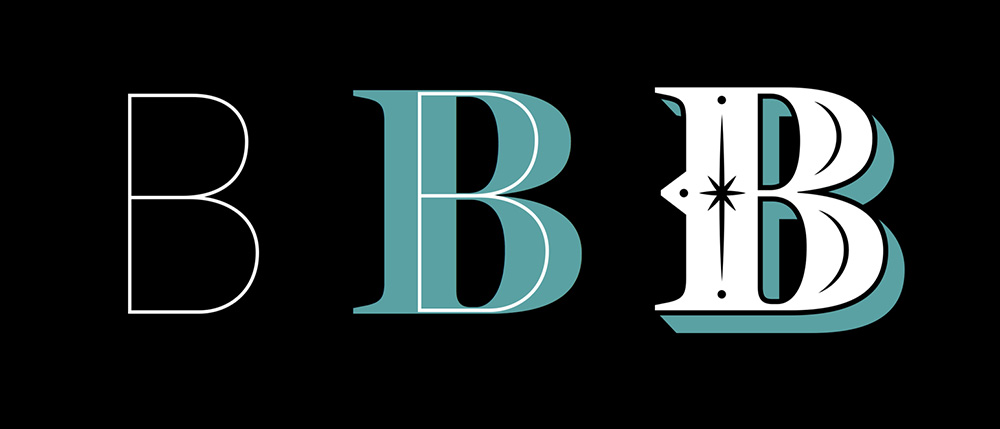

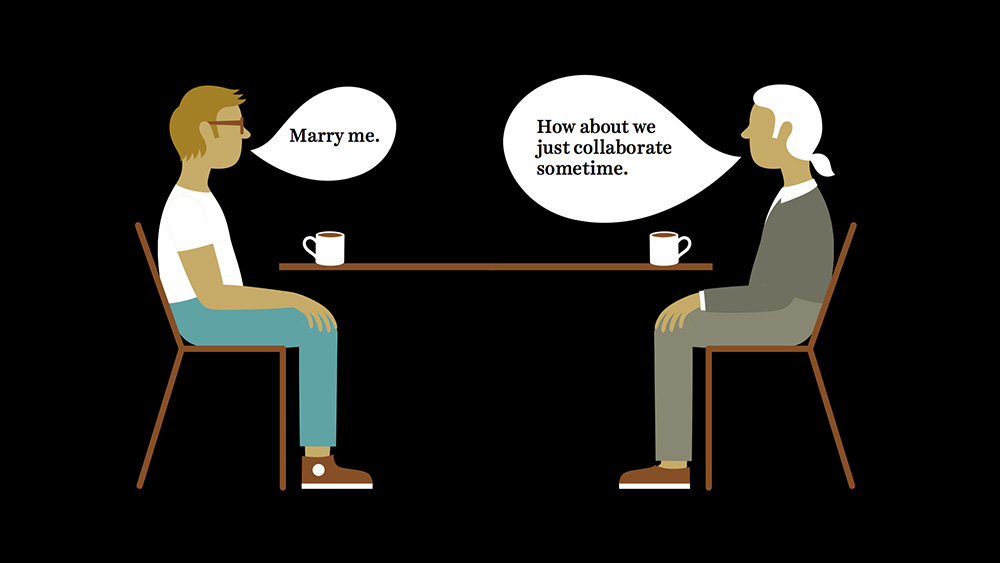

Web designers are familiar with “easter eggs”—the little things they build into the code for people in the know to see and delight in. Well, almost everything type designers make is an “easter egg” in one way or another, because most people think a typeface is just 52 letters, some numbers, and a few punctuation marks. Both groups of people, if they’re good at what they do, go above and beyond to make something amazing, even though most people have no idea what a “contextual alternate” is or would never notice that you’ve made two sets of images, one for retina and one for non-retina displays. Now that you, the web designer, are about ready to add “seeking type designer” to your OK Cupid profile, I’ll get into why it matters to know the people behind the fonts you’re using.

On Type Designers and Favorite T-Shirts

Before I introduce you to a few type designers, I’ll answer the question that every person in the type world is asked—“What’s your favorite font?” If you are a designer of any sort, you’ve probably been asked this question more than once. I know there are plenty of people that can easily name their favorite typeface (usually Helvetica) but I’m not one of them. I’m a believer that if you have a favorite font, you’re probably using it inappropriately or way too often.

Think of typefaces as items of clothing and your self-proclaimed favorite font as a hilarious ironic t-shirt. You love that t-shirt. You think you look like a goddamn model in that t-shirt because it fits like a glove and it’s the perfect amount of thread-bare. Maybe that t-shirt has even gotten you laid a few times. No matter how amazing you think that t-shirt is, if you wore it every single day and to every event, be it a happy hour or a black tie affair, people would start to notice. You’d probably get gentle remarks from your friends about how you should expand your wardrobe horizons from time to time. Strangers might think it’s the only t-shirt you own and that you’re some kind of mysteriously well-groomed homeless person. The other thing about your hilarious ironic t-shirt: it was cool like five years ago but now we all think it’s boring and dated. Don’t have a favorite font. Do have a favorite type designer.

Since I’m comparing fonts to t-shirts, I’ll compare type designers to fashion designers. While it’s ill-advised to wear the same item of clothing every day, it’s absolutely normal to have a favorite fashion designer (or several favorites). If you fall in love with a pair of pants one season, chances are that next season you can buy pants from the same designer and be similarly pleased.  Maybe you only buy shirts from one designer because they perfectly hide that Freshman 15 you’re still trying to rid yourself of at age 30. Maybe you only buy shoes from one designer because they are the only shoes you’ve ever owned that don’t give you a foot-sized blister. Either way, you know you can go back to those designers time and time again and find something you love and that works perfectly for you. If you get to know the type designers that make things that you love, you’ll never run out of beautiful typefaces to work with.

Maybe you only buy shirts from one designer because they perfectly hide that Freshman 15 you’re still trying to rid yourself of at age 30. Maybe you only buy shoes from one designer because they are the only shoes you’ve ever owned that don’t give you a foot-sized blister. Either way, you know you can go back to those designers time and time again and find something you love and that works perfectly for you. If you get to know the type designers that make things that you love, you’ll never run out of beautiful typefaces to work with.

A few type designers I love:

-

H&FJ

Jonathan Hoefler & Tobias Frere-Jones

H&FJ have an incredible reputation for making beautiful text type. You probably know them best from their typefaces Gotham (embraced by the Obama campaign) and Archer (originally commissioned by Martha Stewart but now used everywhere.) I love these guys. And I use their fonts on my site.

-

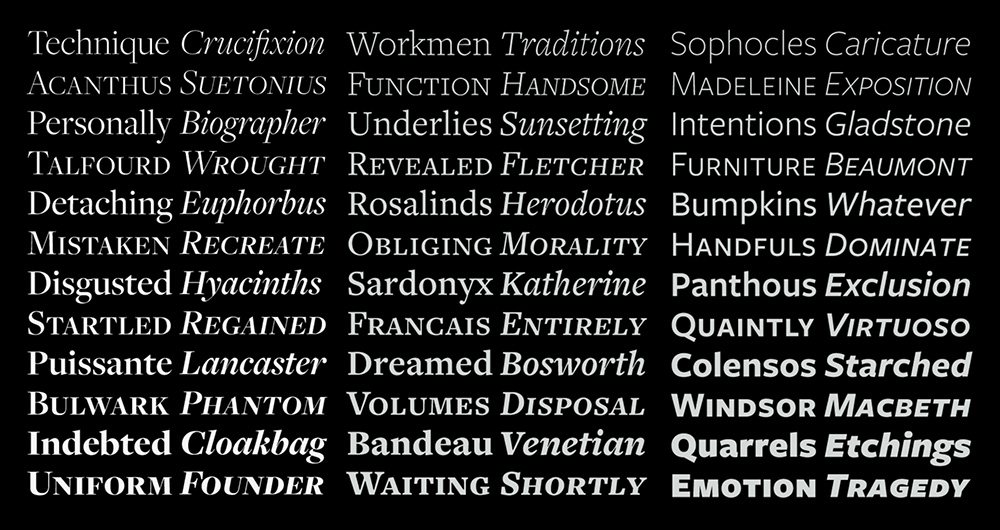

If you’ve seen me speak in the last year, you’ve seen me use Jackson’s beautiful Harriet Series all over my presentations. The slides in this post use his typeface extensively. I love everything this man makes and when he showed me Harriet for the first time I wanted to both punch him in the face and kiss him on the lips.

-

Underware

Akiem Helmling, Bas Jacobs & Sami Kortemäki

You’re probably familiar with their typeface Bello but there are so many others worth checking out. I’m a big fan of Dolly, which is a very friendly serif, and Liza if only for the opentype insanity they programmed into it.

-

Josh and his studio make incredibly beautiful typefaces, including Freight, a serif super family and Omnes, a rounded sans that has a wonderful weight range and great personality.

-

I first became familiar with Mark’s work because of his typeface Coquette. His sans-serif display face Mostra Nuova is beautiful and vintagey and he has a slew of other great faces. Also, his website is lovely.

-

When I judged the TDC Type Annual a couple of years ago there was one typeface that made me say to myself “I can’t wait to go home and use that!” That typeface was Brandon Grotesque. Since then Hannes has released a few other faces including Pluto and Pluto Sans.

-

Type Together

Veronika Burian & José Scaglione

With typefaces like Abril and Bree under their belt, these guys can do no wrong. I think my favorite of theirs (right now) might be Maiola though. Goddamn I love that typeface.

-

I don’t know a single type-centric person that won’t praise the abilities of Kris Sowersby. He’s a young kiwi that’s released a string of hits including National and Founders Grotesque, and I love Galaxie Copernicus, which is a super pretty serif.

-

Lapture from JAF is a beautiful and weird text face and Herb is one of the coolest typefaces ever. These guys make beautiful type with the right amount of personality.

-

House Industries

Rich Roat, Andy Cruz, Ken Barber, & Others

You couldn’t spit without hitting one of House’s typefaces in my college design department. They specialize in fun and funky display typefaces that are beautiful and well built.

-

Commercial Type

Christian Schwartz & Paul Barnes

Christian and Paul have some truly beautiful typefaces and have carved out a niche in the newspaper industry for producing excellent newspaper type. Their talents don’t stop there though, check out Marian, a lovely hairline that, while impractical for the web, is still worth appreciating.

-

If you got married in the last five years, chances are high that you used one of Ale’s typefaces on your wedding invitation. If you love to play around with swashes, his fonts are for you.

-

MVB Fonts

Mark van Bronkhorst

Mark’s Sweet Sans is one of my favorite faces—I’ve always loved Engravers’ Gothic but found myself wishing it came in more weights or just had a bit more to it and then Sweet Sans debuted to answer my prayers.

Choosing the Right Type

There are some beautiful typefaces out there, but not all of them will be perfect for your project. If you’re a web designer, especially if you’ve attended past AEA Conferences, you have already heard a lot about putting the content first and making websites that don’t sacrifice legibility and ease of use for fluffy ornamentation. Figure out what kind of content is most prevalent in your project (more often than not plain ol’ body copy) and choose the typeface that satisfies the needs of that content. This first typeface you’ll choose is your anchor, a term I’m borrowing from Tim Brown’s little compendium of knowledge Combining Typefaces, which is an excellent and very quick read. All other typefaces you select must first pass the “does this jive with my anchor” test. Remember that just because a giant headline is the first thing your reader sees, that doesn’t mean it should be the first typeface you choose.

There are a bunch of things I take into consideration when choosing a text face that help me narrow down the candidates. Here’s a list of credentials a typeface must pass for me to want to use it as a text face:

-

Does it come in a variety of weights?

Being able to play with weights is incredibly important to me when I design. I’m not satisfied with the standard three weight set of light, regular, and bold. I like to work with typefaces that have inbetweener weights and if possible the full range from 100-900 just so that I have more flexibility while designing. Sometimes I want text to feel a little bolder or more emphasized but I don’t want it to be “bold”. Sometimes I want to set text at different sizes but maintain an even text color. Also, the more weights you have the more flexibility you have with color choices and reversing type out of image—you won’t have as many issues with how anti-aliasing affects the perception of type weight. I know that using a lot of fonts (each weight of a typeface is considered 1 font) can affect page load time—talk to your web font service about how you can streamline your site so that using multiple fonts doesn’t slow things down.

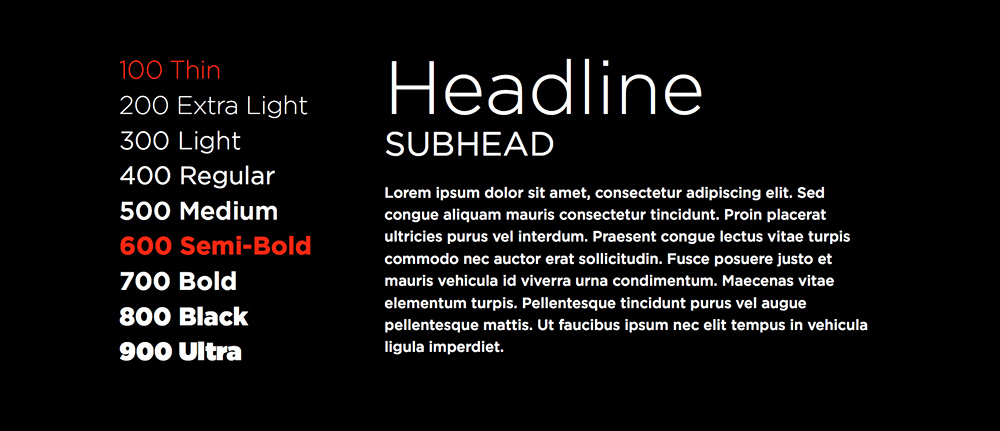

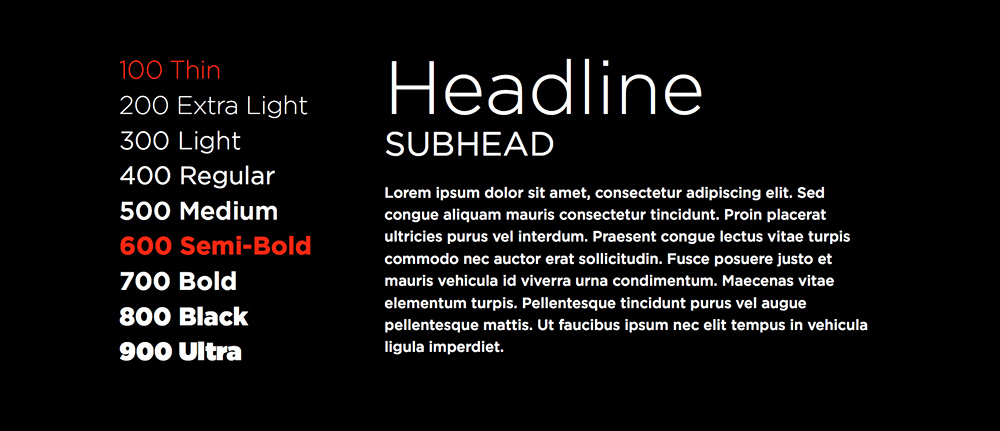

Gotham comes in eight weights (I own it in seven, hence the two red weights that either aren’t available or aren’t in my library), here’s how desktop definitions of weight might compare to web-friendly numbered weights.

-

Does it have a nice x-height?

A generous x-height (the height of lowercase characters) is very important when choosing a text face. If the x-height is too low, the typeface will appear smaller overall and the caps will have too much emphasis which interrupts smooth reading. If the x-height is way too high, your eye won’t be able to distinguish quickly between caps and lowercase, which can make you lose your place while reading. A generous x-height allows you to set type at small sizes (for captions and the like) and have it still be very legible.

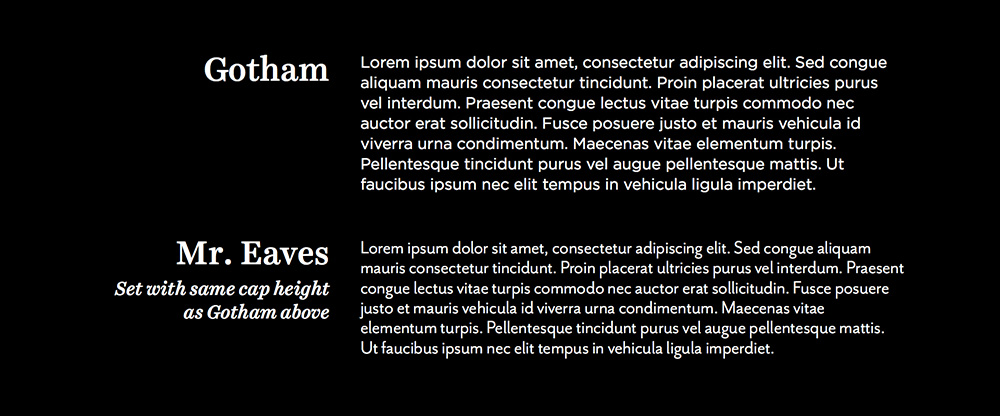

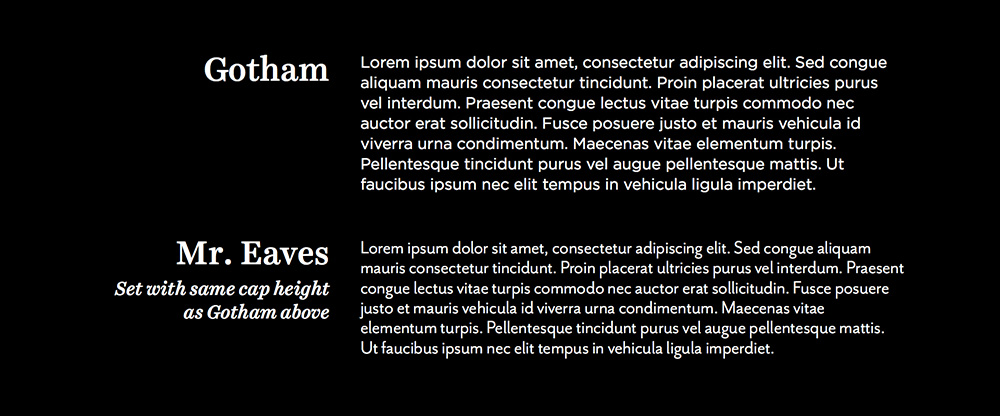

The x-height line shows just how much taller Gotham’s x-height is compared to Mr. Eaves.

Mr Eaves looks smaller in comparison even though their cap heights are the same.

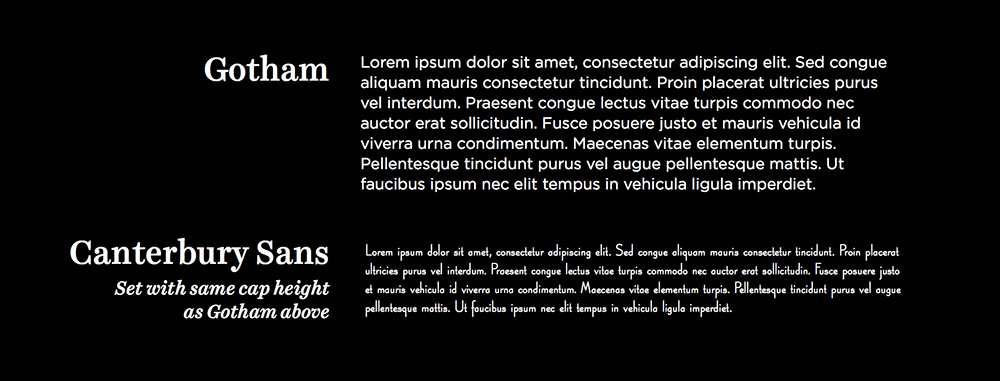

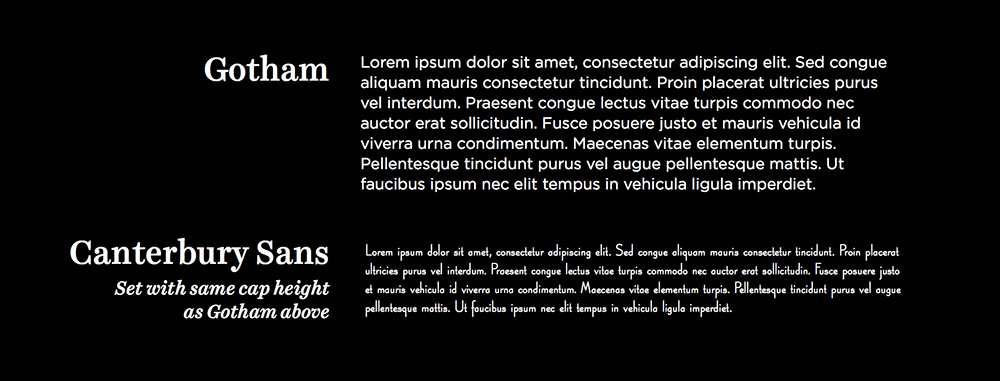

Canterbury Sans could never be used as text type. Its very low x-height makes it a poor candidate for body copy.

-

Does it have a true italic?

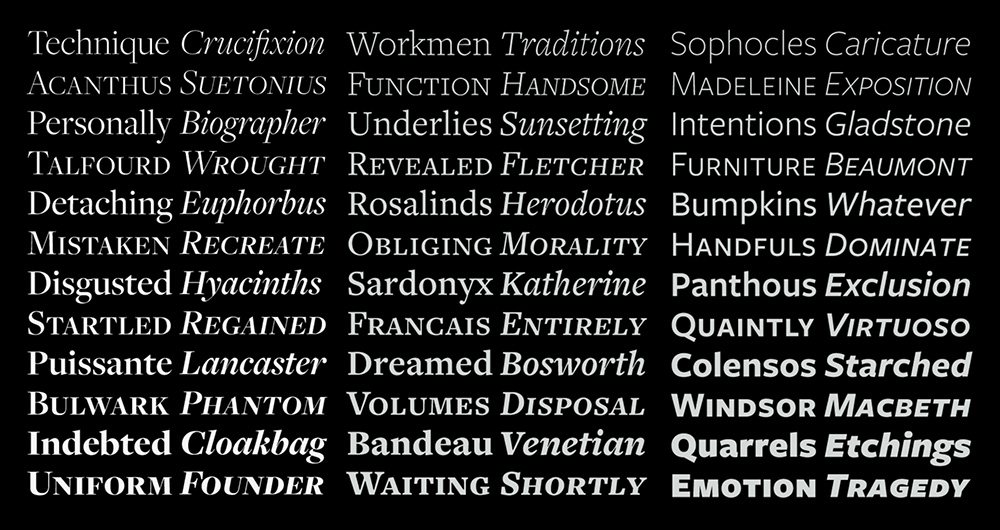

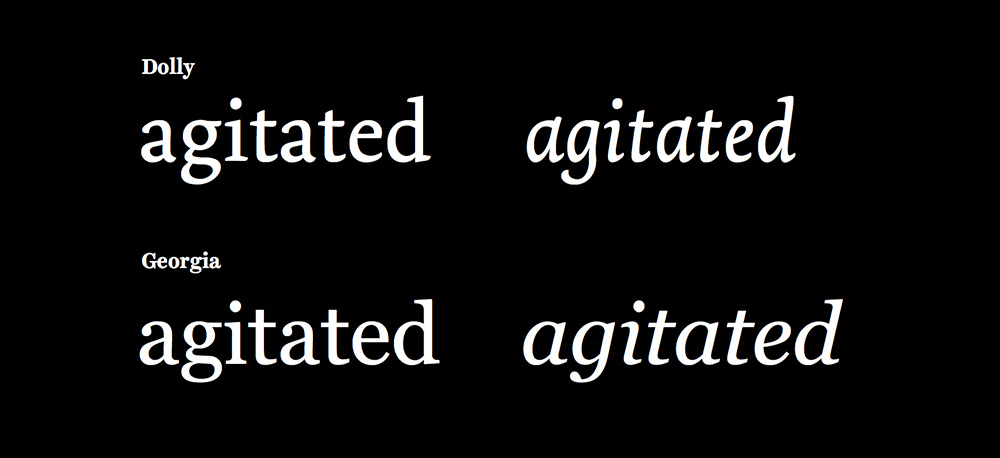

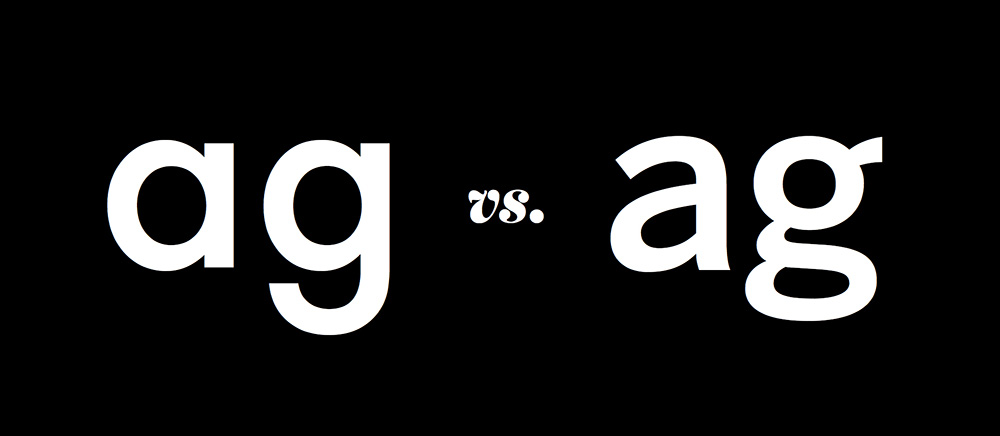

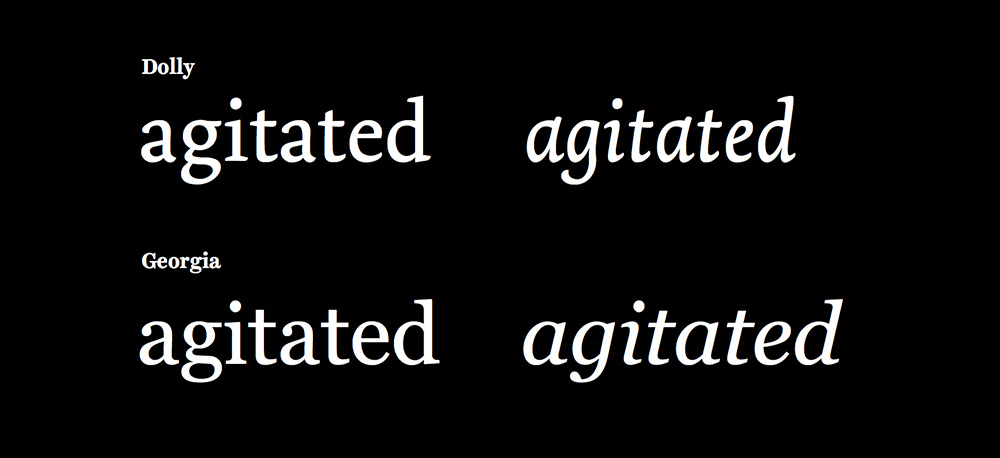

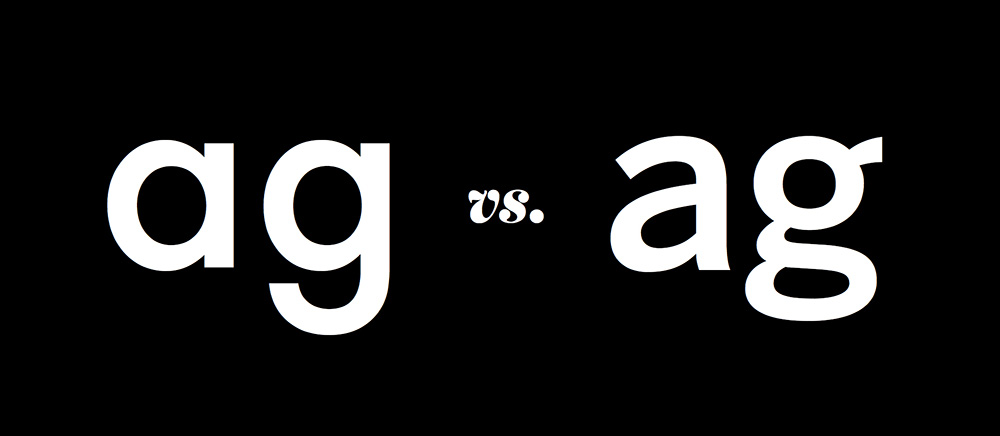

There’s a difference between a sloped roman and an italic, and that difference means the world to me. I love typefaces that have really lovely true italics that are easily identifiable in blocks of text. What makes an italic an italic is that its structure is more closely related to scripts or writing than a roman—it has identifiable entrance and exit strokes rather than perfectly symmetrical serifs and usually has a single story a and g. True italics also ensure even color (matching weight) within text when used with their roman counterpart. I love italics. Italics will be my gateway drug to text type design when I make the leap from lettering. Georgia’s italic is one of the reasons that typeface will always win for me over other standard serif text faces.

The letterforms for serif italics can be quite different from the roman letterforms. In sans-serifs, the difference is often less extreme.

-

Is it a typeface I’d want to hang out with?

Typefaces definitely have personalities and I’ll get into ways to conceptually brainstorm about type shortly. When it comes to text type, I usually want something even-tempered and laid back but not lacking in personality. Finding typefaces with the right personality balance can be incredibly difficult because if you add even the most minor bits of flair to a letter—even the slightest curvature to a serif—it can make the type feel like it’s sporting a screaming purple mohawk when set in paragraph form. Sometimes you want your type to sport a screaming purple mohawk, but I can confidently say that those times don’t happen often. I should also note that “screaming purple mohawk” is relative. What I consider to be a screaming purple mohawk, you would probably consider the most subtle nearly invisible change in tone. You are the husband that won’t notice I got a haircut unless I chop it all off and blondify myself.

Some other things I consider while choosing a text face:

-

Is it spaced well?

Text type requires looser spacing. Display requires tighter spacing. One reason Helvetica (the version you all have on your computers) doesn’t work well for text is that its letter-spacing is just too damn tight. If you feel like you have to add letter-spacing to 16px body copy, you might be working with a typeface that is too tightly spaced, or too tightly spaced for your taste. The white space within and surrounding a letter is incredibly important to the overall design of the type, just as important as the black parts—spacing can absolutely make or break a typeface. Cyrus Highsmith has a great section about establishing good spacing within and around type in his book Inside Paragraphs, which is a very quick read and a great intro to typographic principles.

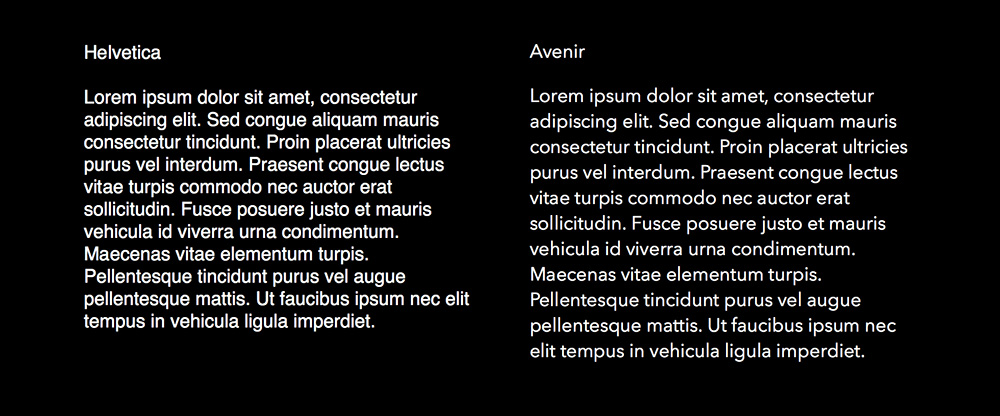

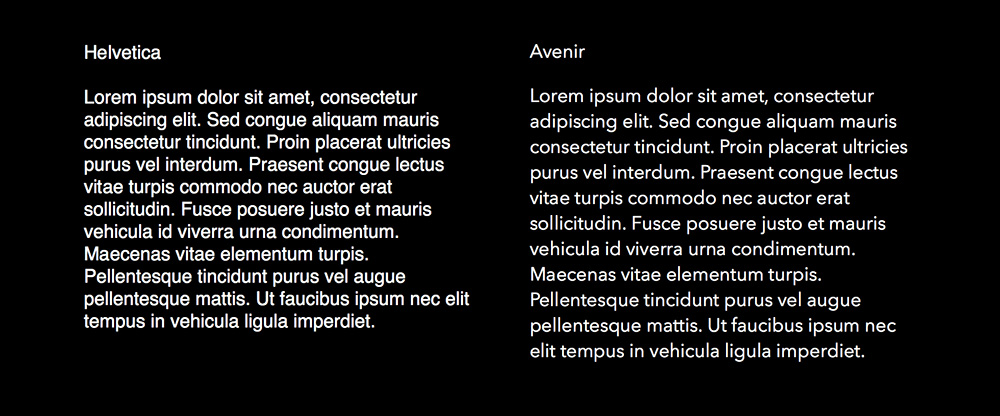

Avenir’s more open spacing make it a better text face than Helvetica.

-

Does it have even color?

Sometimes when you stare at a block of text some letters pop out to you more than others because the letter looks heavy where separate components (like a stem and a leg) join together. This can make type feel spotty and any good type designer will prevent this from happening by making little micro adjustments to the letters to make sure that they don’t feel optically heavier at the joins. Most of these changes are imperceivable by the average viewer—and they should be—but they make a world of difference to the type.

Notice how the stem on the n is less wide at the top to compensate for the weight at the join.

Consistent type color also has a lot to do with the counters, or the spaces within the letters. If counters are too closed, it can make a letter seem heavy or affect legibility and letter recognition. There’s some saying about how beginners design with black-space in mind and experts design with white-space in mind, but I forget the exact wording. You get the point.

-

What width or widths do I need?

Some typefaces come in a variety of widths (Narrow, Condensed, Regular, Extended, etc.), but when I talk about type width I’m not only talking about these drastic style changes within a family—I’m also talking about the difference in letter width between different “regular” width typefaces. You probably have a natural preference for certain type widths (I tend to like wider / more round feeling widths than narrow ones) but there are appropriate times to use type of all widths. If you’re designing a website with narrow text columns, you might want to pick a typeface whose regular width is a little on the narrow side so you can get more words on each line without having to scale text down, which helps keep hyphenation reasonable and type more legible. If you have a site that has columns with vastly different widths, finding a typeface that comes in a variety of widths can be incredibly helpful so you can use narrower width type on narrower columns and normal width to ever so slightly wide type on wider columns. The goal when setting type is to make it beautiful and readable, and one of the things that helps with legibility is per-line word-count. Choose typefaces that lend a hand in getting the right amount of words on a line.

-

If it’s a sans, is there enough letter variety?

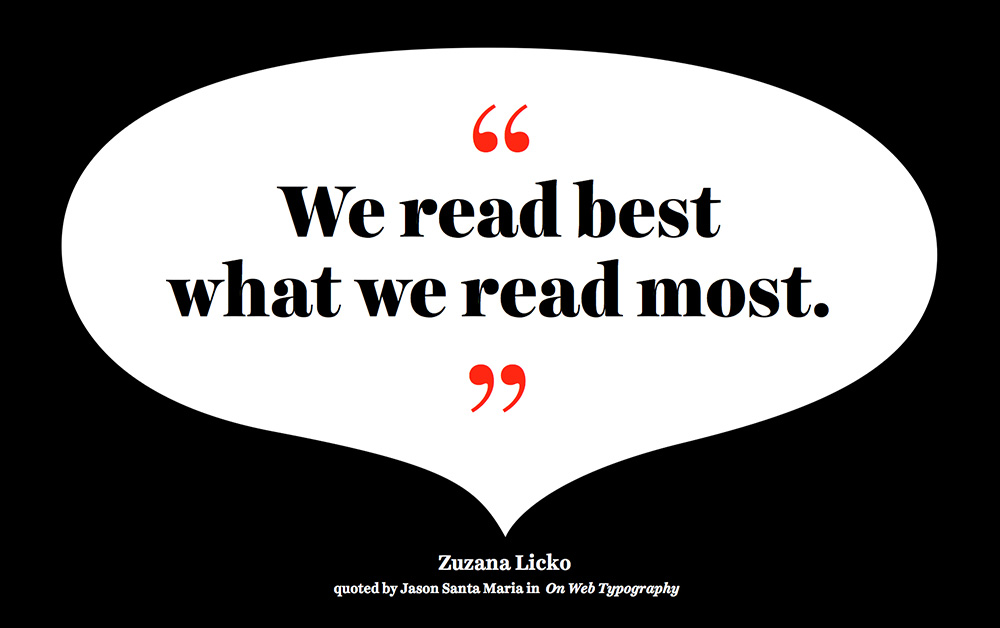

Using sans-serif typefaces for body copy can be a little tricky because without serifs it can be more difficult for the eye to quickly distinguish between two similar letter forms. I’ve used the term “legibility” more than once already, and while I won’t go off on a tangent on what makes a typeface more or less legible, I can say that it’s all about pattern recognition. In his 2009 article “On Web Typography” for A List Apart (which was expanded upon for an upcoming book), Jason Santa Maria quotes Zuzana Licko who stated “We read best what we read most.” Perhaps 50 years from now, Helvetica will be considered the most legible typeface on earth because of the insane Helvetica fetishism we’ve witnessed over the last few years, but for now our (western) eyes and brains are trained to skim quickly and effortlessly over serif typefaces and recognize patterns and shapes within the letters.

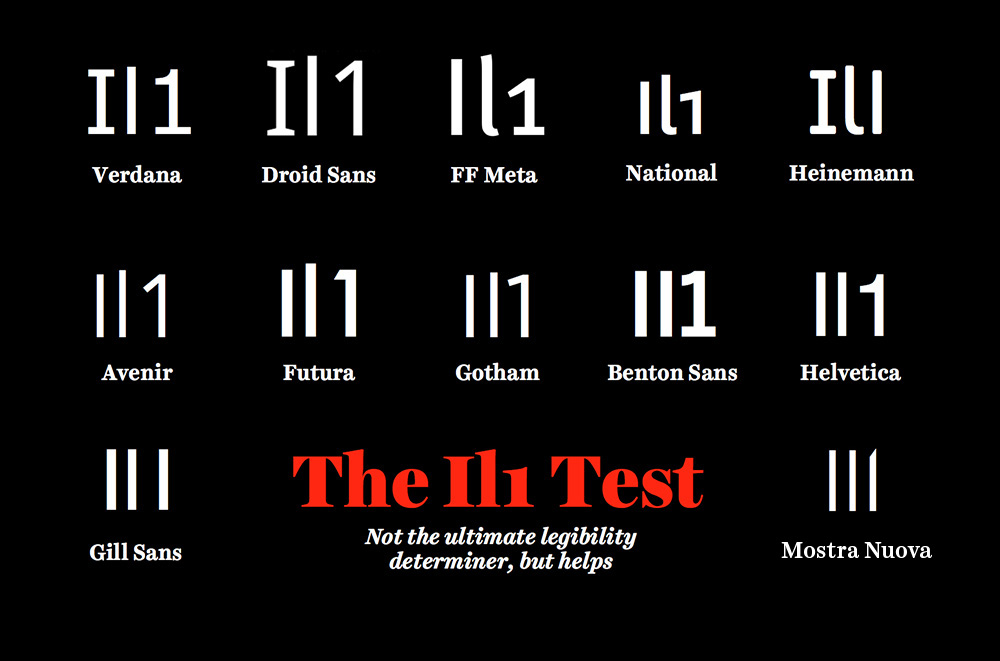

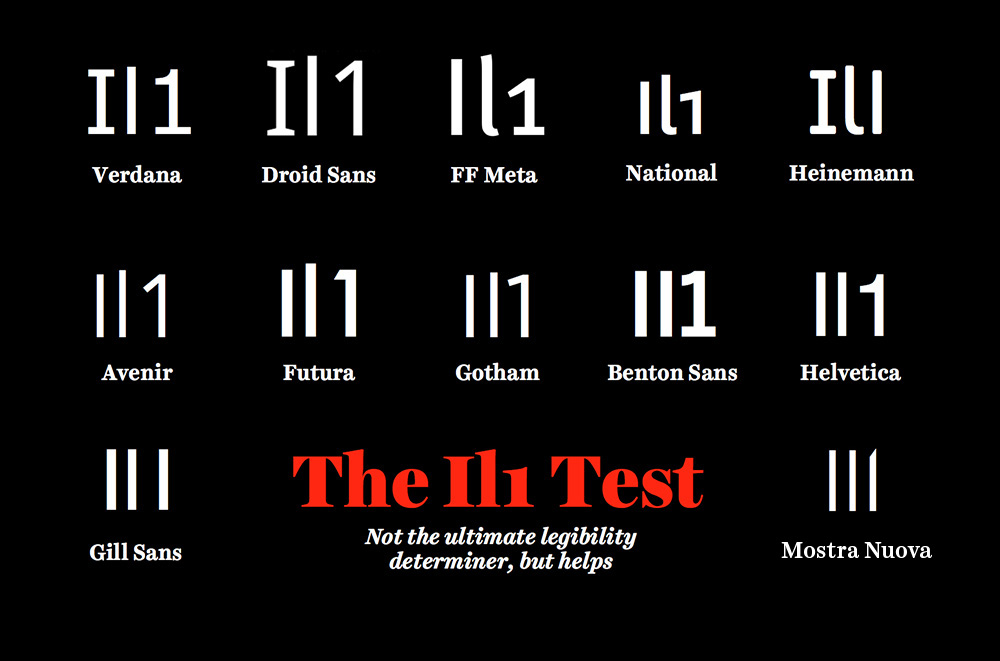

I try to find sans-serifs that pass the Il1 rule. Type a capital I a lowercase l and a number 1 next to each other. If you can’t tell the difference between these characters, you may run into some trouble when setting the text. There was a fake London2012 twitter account posting some incendiary things this year that looked completely legit because the sans-serif twitter uses (Helvetica Neue) doesn’t pass the Il1 rule. The account was actually London20l2 but no one could tell the difference. Also check to see if the typeface has a two-story a and g. Sans-serif typefaces with two-story a’s and g’s usually read a bit quicker than those with single-story a’s and g’s. All this said, 90% of the time I choose serif typefaces for body copy.

Where do I find good type?

You guys are in luck. Since I don’t work for one of the main web font providers unlike almost all people that write about web fonts nowadays, I can give you a bit of a different perspective about web font services. There are a variety of options out there and each has its own pros and cons. First, it’s probably good to understand the difference between hosted and self-hosted fonts.

Hosted vs. Self-Hosted Web Fonts

Hosted web fonts are definitely the easiest to implement and usually just involve adding a line of JS to your site in the head in order to install. You then just have to follow the provided instructions for calling the fonts in your CSS and you’re ready to roll. I prefer hosted web fonts because they’re incredibly painless to set up.

Self-hosted typefaces put more control in the designer’s hands but are a little less effortless to install. If you are a control freak, self-hosted fonts may be for you. One of the major disadvantages with self-hosted web fonts is that if the type designer chooses to update the typeface, you must manually update the typeface on your site (upload new files to your host) vs. a hosted service which will update the files automatically (sometimes prompting you to “republish your kit”). One of the major advantages of self-hosted web fonts is that if the type designer updates the typeface you must manually update the typeface on your site, leaving it up to you to decide if you want to update. You see what I did there?

Some Common Web Fonts Services

-

You guys are probably all pretty familiar with Typekit since they sponsor a lot of web related events and have one of the bigger presences in the web font world. Typekit uses a library subscription model for typefaces, which is absolutely wonderful for web designers. For a low monthly fee you get access to a large library of typefaces and can create endless “kits” for all of the websites you work on. The team of people behind Typekit goes above and beyond to make browsing for fonts easy and fun and they post very handy articles on their blog. Sometimes I feel like I should be sending Typekit extra money because they’re so inexpensive it feels like I’m stealing from them. That said, anything that is cheap for you the user is probably also not returning a ton of dough to the type designers. While I love Typekit, and use them all the time, there are definitely web font services that have a payment structure that leans more in the favor of the type designer than the consumer.

-

Webtype is run by some true type nerds over at Font Bureau. While they don’t have the biggest library, they do only serve up quality typefaces and specialize in the texty end of the spectrum. If you value quality over quantity this is the service for you. They do endless testing and tweaks to make sure everything looks amazing on both Mac and Windows. Type is rendered differently on Windows than it is on Mac, so sometimes something that looks beautiful and smooth on Mac looks completely weird and janky on Windows. Webtype goes to great lengths to make sure this doesn’t happen and that their type looks great even in the harshest environments. One of the main advantages of using Webtype over other font services is that they are actually designing / commissioning typefaces to be made specifically for web, rather than adapting print typefaces to a web environment.

Webtype is not a library subscription model, you pay individually and annually for each font you use on a site (pricing based on page views), but the fees are still quite low for what you get. This is definitely a pricing structure that is more in favor of type designers, but they do what they can to make it painless and inexpensive for the average user. Like most services with this pricing model, they do allow a free one month trial for their fonts so you can see everything in place before committing. You can also buy a perpetual license for typefaces, but most people opt to license for limited time periods if they foresee a redesign a few years down the road or want to save a little dough.

-

Fontdeck is similar to Webtype in its pricing structure—you pay per font per month based on average page views and there’s a free trial period to test typefaces before you commit. They have a wide selection of type and seem to focus more on quality over quantity, carrying a lot of the classics but also a good mix of new solid typefaces. Like Typekit, Fontdeck was founded by a group of enthusiastic web nerds with a passion for typography and also like Typekit, they’re very easy to use / install and offer both a JS (recommended) and an HTML option for font installation.

-

Fonts.com has an enormous library of fonts and has a pretty compelling marketing page. They stress how forward-thinking they are in terms of open-type support, that they have the best font selection with over 20,000 typefaces, and that they have unparalleled language support. It looks like at one point they priced their typefaces individually but are now offering a subscription model and their top tier subscription includes access to unlimited desktop fonts (a library of over 7,000 typefaces) delivered through a proprietary system called SkyFonts.

-

I haven’t personally used WebINK (yet!) but Thomas Phinney had some great things to say about it and he listed some features that many of you will find appealing: it does not require JavaScript for fonts to work (though you can still use JavaScript to suppress the dreaded Flash of Unstyled Text or “FOUT”); [he states that there is a] higher quality bar than Typekit or Google Web Fonts; there are over 1000 families, 5,000 fonts; 80% of WebINK fonts are enabled for Photoshop for purposes of comps and mockups via a plugin—once activated in Photoshop they work just like other fonts, no weird or awkward limitations. (Also enables Google Fonts in Photoshop.); the FontDropper bookmarklet allows users to try any WebINK fonts on any web page, live—including ones you are working on.

-

MyFonts is like a mega department store for type and like any mega department store not everything they sell is amazing. There’s some beautiful high end stuff on there but also some dreck. Also, they’re completely fine offering web font licenses to any typeface (with the designer’s permission of course) even if the typeface was not originally intended for web font use. Some fonts are offered as a perpetual license (which means you pay more up front but aren’t charged annually) and some are offered in a semi-subscriptiony way where you pay for page-views and have to re-up once you hit your limit. I know from personal experience that their self-hosted method is not the easiest to implement.

-

I’ve said some disparaging things about Google Fonts in the past, mostly because I think type designers already have a hard enough time getting paid so their “everything is free forever” model bothers me. Don’t start with the whole “the internet should be a place for a free exchange of ideas” line, and I know plenty of you guys think we should open-source everything ever, but type design is one of those professions that really does take a lifetime of experience to master and every typeface takes endless hours and sometimes years to create. The typefaces available through Google Fonts were made by type designers that were paid a one time flat fee for their work along with the promise of exposure to a large audience (and we all know how I feel about that incentive). Because of this fee structure, the fonts that are good often only come in one weight or aren’t available with an italic. All this said, it’s definitely one of the easiest services to implement on your site since there’s no need for a membership, login, or payment. I shake my fist at them for making something so easy to use that I have to dislike on principle.

-

Other Services and Options

It’s not my intention to make a comprehensive list of all web fonts services out there, and there are plenty of others including those set up by individual foundries. On my website, I use H&FJ web fonts, which are not yet available to the general public but will be soon. I definitely advise that if you fall in love with a typeface and notice that it’s not available through any of the major web fonts retailers, contact the designer to see if there’s a way for you to use their font. Also, if you notice a typeface is available through multiple retailers, you could do the type designer a serious solid by contacting them to see which of the services offers them the best cut of your cash. Above all, remember that working with type retailers and designers that focus on quality over quantity is key. The more browser/platform testing and insane perfectionist nonsense foundries do before they release a font, the better. You get what you pay for, and sometimes you end up “paying for” free fonts in different ways. Testing type in different conditions will always be necessary, but if you choose high quality fonts less of the testing will fall on your shoulders.

Thinking Conceptually

Defining the Mood

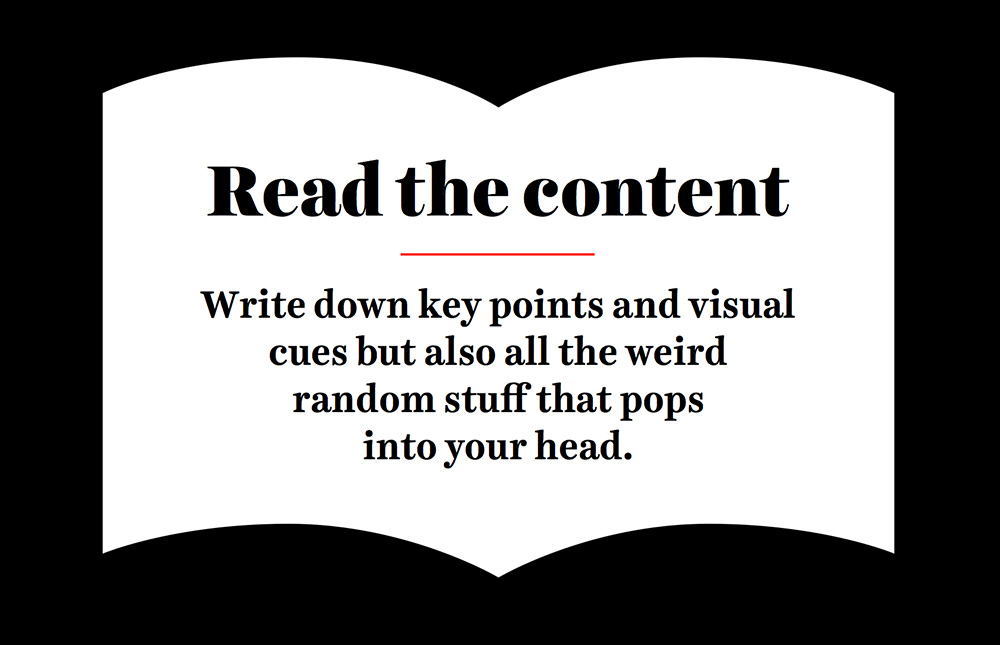

Alrighty, now that you know where to look and have established some general guidelines for what you are and aren’t looking for in an anchor typeface, you can start getting a little arty. Brainstorming for type is not dissimilar to brainstorming for an editorial illustration or a book cover. If you’re commissioned to create a book cover, first you have to read the book.  As you read, you write down key points and visual cues you might be able to pull from in the future—not just plot points and character names that could easily be found on Wikipedia, but also notes about how the text makes you feel. What are the characters like? What mood does each scene convey? You can even write down random words that pop into your head that seem completely unrelated to the book. Some deep crevice of your brain thinks those words may be relevant, and since you’re only brainstorming why hold yourself back?

As you read, you write down key points and visual cues you might be able to pull from in the future—not just plot points and character names that could easily be found on Wikipedia, but also notes about how the text makes you feel. What are the characters like? What mood does each scene convey? You can even write down random words that pop into your head that seem completely unrelated to the book. Some deep crevice of your brain thinks those words may be relevant, and since you’re only brainstorming why hold yourself back?

I’m a huge fan of word association lists. I don’t make pretty “mind maps” where I try to draw visual connections between my thoughts, I just let my mind wander and write down any word that pops into my brain when reminiscing about a book I just finished or when brainstorming for a company’s logo. The less pretty and organized this list is, the more likely I am to actually let my mind wander. After I’ve exhausted every possible banal and bizarre thought point, I think about which of these words would be an a-ha moment for a savvy reader, sometimes voltroning a few words together to create a very unique and unexpected concept.

Sometimes pop culture attaches associations to type that are hard to shake. Most people think about Cooper Black as embodying the 1970s aesthetic despite the fact that it was created in the 1920s. Blackletter, before it was embraced by every Hot Topic-shopping high schooler, was just a fancy laborious way people wrote in the 12th century. Type without immediate cultural associations can definitely evoke a feeling and a backstory, you just have to spend enough time with it to let that story materialize. Most people aren’t used to thinking about type conceptually, and it’s absolutely more difficult to design with abstract forms rather than narrative images. Just because it’s easy to find shitty stock photos of ethnically ambiguous business men shaking hands on top of a globe doesn’t mean our conceptual thinking should stop there.

Establishing Historical Context

Sometimes you’re working on a project and you can add another layer of conceptual fun by sticking to type that was created during or accurately references the historical period your project is meant to convey. If you were making a porn website that specialized in films created between 1980 and 1985, wouldn’t it be fun to choose a text face that was created during that time frame? It wouldn’t need to be some crazy shoulder-padded display face, just a subtle wink to the era. I worked on a project with Google recently, and while I had to use some Google Web Fonts which were modern interpretations of type that could have existed in the 1920s, I did convince them to license Cheltenham as the main typeface. Cheltenham had the right amount of personality for the project and was made in the very early 20th century so it was totally feasible that it could have been used in the films.

Trying to be historically accurate is one of those things that will go unnoticed by most folks, but as we established earlier you don’t care that most people won’t know the extent of your labor—you’re happy that there are a few true nerds out there that will be tickled pink by your efforts. I should also probably mention that if you do make a very wrong decision when it comes to type, non-nerds will notice, they just won’t know how to verbalize what’s wrong. I like to compare making a typographic mistake (like accidental inverted stress on a letter, which is when the thickness is in the wrong place) to having an eye a half-inch higher than the other on your face. People might not be able to place right away what it is, but something about your face isn’t quite right.

When I worked on the typeface for Moonrise Kingdom, trying to find a script that felt true to the time was a little tough—most of the script typefaces that came out in the late 50s and early 60s (the story takes place on a small island in New England in the early 60s) were brush scripts, which didn’t feel right for the film. We had to reach a little earlier, into the 40s, to find something that made sense. Typefaces from the 40s would totally have still been in use in the 60s, especially in a small conservative town in the northeast. This sort of conceptual reasoning in typeface selection is something that clients love to hear about and can help you convince them to think beyond the standard “web safe” typefaces. The more you know about the typefaces you’re using, the easier it is to justify their use.

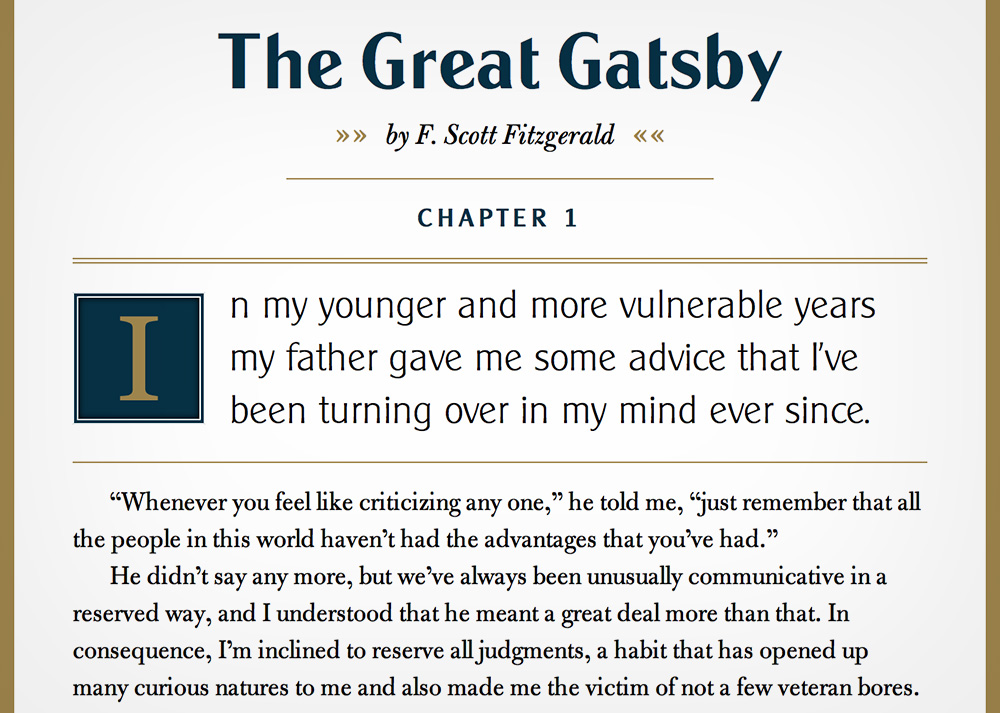

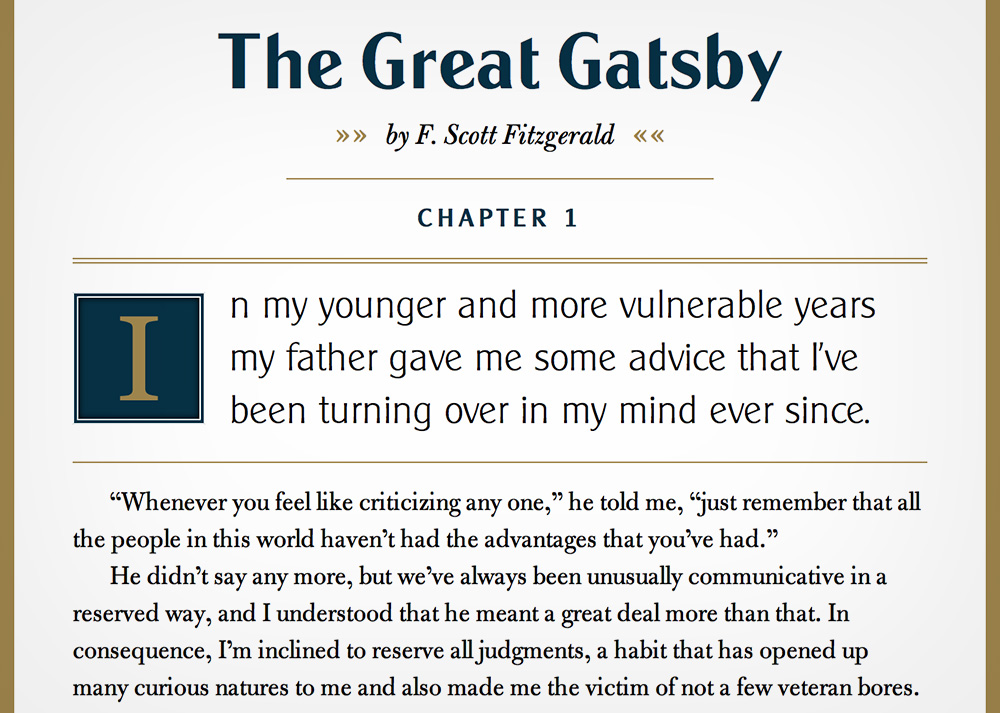

I created a little type sample—typesetting the title and the first few paragraphs of The Great Gatsby—to show you how historical accuracy can add an extra layer of oomph to your design. There are four versions, a completely un-styled version, a fully styled version that uses the default typeface Georgia, a version using typefaces that people perceive as being accurate to the time but are a little off, and a version using historically accurate typefaces. I also targeted the text differently in each version so you can see different ways to apply CSS to text. While the “somewhat accurate” version might scream 1920s a bit more loudly than the historically accurate version, there’s something nice about making historical references that are more subtle and less cartoonish. The reason why everyone throws up rainbows about the set design and costumes on Mad Men is because they go above and beyond to show more than just the most iconic designs of the 50s and 60s. Also, by using typefaces that are accurate to the time we don’t run the risk of rewriting history and adjusting the public perception of what design from that era looked like.

Pairing Typefaces

You can absolutely design an entire website with just one font family, but why miss out on all the fun of font-pairing? I’ll bring up the fashion design analogy again—if you dress head to toe in Paul Smith you’ll look sharp as a tack but you’ll also look like a walking advertisement for Paul Smith. Good fashionistas and good typographers flex their curatorial muscles by putting together items in unexpected combinations that lead to beautiful and harmonious (or purposefully discordant) results. (On a side note, I love making this fashion design analogy over and over again to a crowd whose wardrobe consists entirely of plaid button-downs and free t-shirts.) Establishing a relationship between two different typefaces can seem like a daunting task, but there are a lot of resources and writing out there to help you figure it out. One of my favorite sites to see good font pairing in action is Fonts in Use and if you want to hear some very smart people talk about pairing typefaces, look for talks and articles by Jason Santa Maria, Tim Brown, and Stephen Coles. Also, never hesitate to ask a type designer to recommend typefaces that will pair well with your anchor. Type designers, like most good nerds, love to share knowledge with anyone that’s hungry for it. Ask them about font pairing, licensing questions, technical questions, relationship advice—anything really. Also, if you can establish a relationship with a foundry or designer, they’ll usually let you try stuff out for free or give you access to early releases of upcoming typefaces.

Here are some tips for pairing typefaces:

-

Choose a Super-Family.

Some typefaces are released as a super family. Super families come with a variety of weights, a variety of widths, and sometimes a sans-serif and serif version meant to complement each other perfectly. Combining fonts from the same super family is definitely the first step to feeling confident mixing and matching typefaces. You can instantly create a harmonious relationship between two fonts this way, which is great if harmony is what you’re after.

Freight Display, Freight Text, and Freight Sans by Darden Studio.

-

Choose Typefaces from the same type designer.

Each designer has a personal aesthetic that shines through in their work, some more obviously than others. If you’re feeling timid about combining very different typefaces, do some foundry research first to find designers you like. If they have a number of typefaces available, chances are there are a few that would pair off well together.

-

Choose typefaces with similar characteristics.

Once you feel like you’re ready to take off the training wheels, try to make type pairings based on what they structurally have in common. To explain how you can establish similarities between two typefaces, I’ll first explain what you should be looking for. Typefaces can be thought about in three parts:

-

The Skeleton

The “bones” of the typeface or the basic frame on which the typeface is built. The skeleton determines the width of the letter, the x-height, and the general proportions of components of the letter.

-

The Meat

The body and weight of the typeface. While adjusting the weight of type can seem like the most dramatic change you can make, the type will still be relate closely to its underlying skeleton. Some typefaces are weighted in different ways than other depending on which tradition they emerged from—translation (broad nib) or expansion (pointed pen).

-

The Clothes

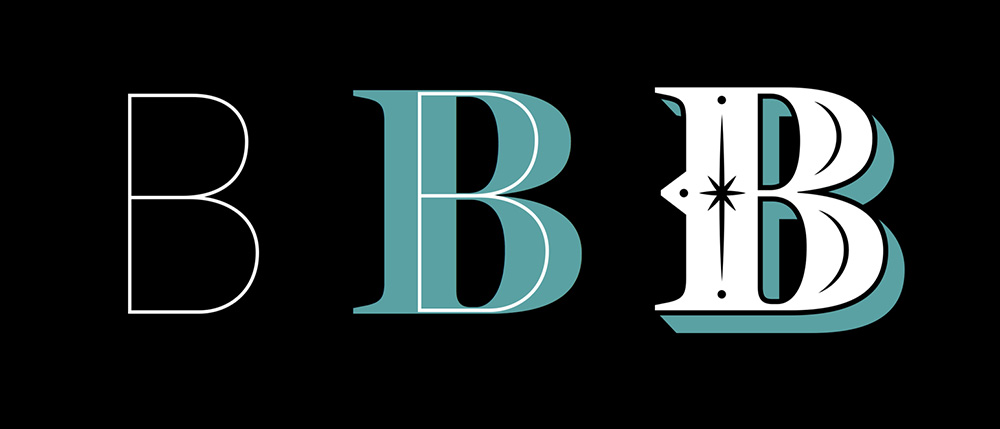

All the fun pizzazz we add to type to make it look awesome. Sometimes serifs can be classified as clothes or meat, depending on how essential they are to the structure of the type. Other things that would be considered clothes are spurs, ornamental serifs, drop shades, drop lines, etc.

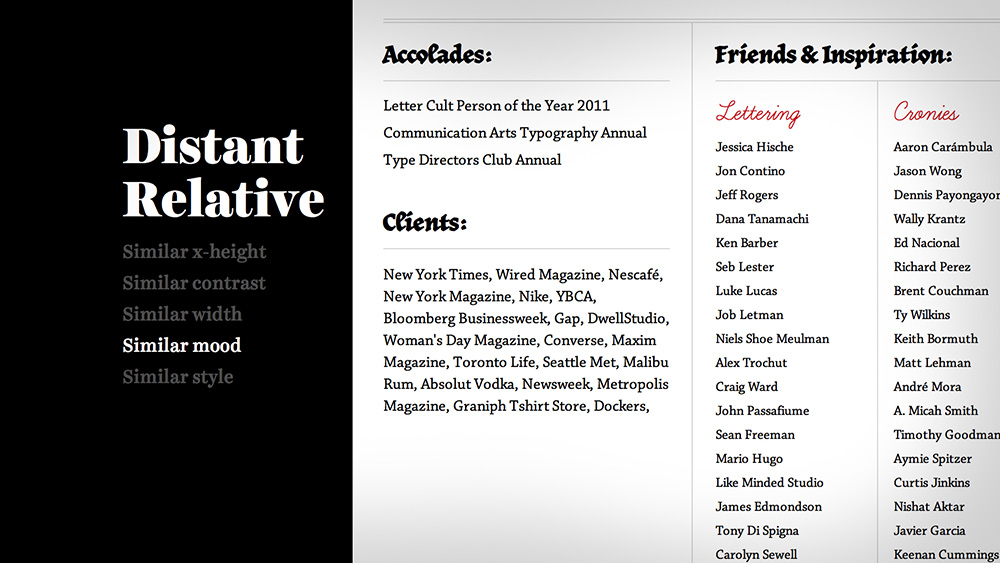

A serif and sans-serif might look spectacular together if they share a similar skeleton—a lot of people recommend this as a place to start. Find a serif for your body copy and a sans for your headlines. Sans and serifs can form an easy harmonious relationship if they have similar proportions (x-height, letter width, bowl shape and structure) and attitudes. I made a little chart of a way to think about the stages of relation between typefaces:

-

Sibling

- Similar x-height

- Similar contrast

- Similar width

- Similar mood

- Similar style

-

Cousin

- Similar x-height

- Similar contrast

- Similar width

- Similar mood

- Similar style

-

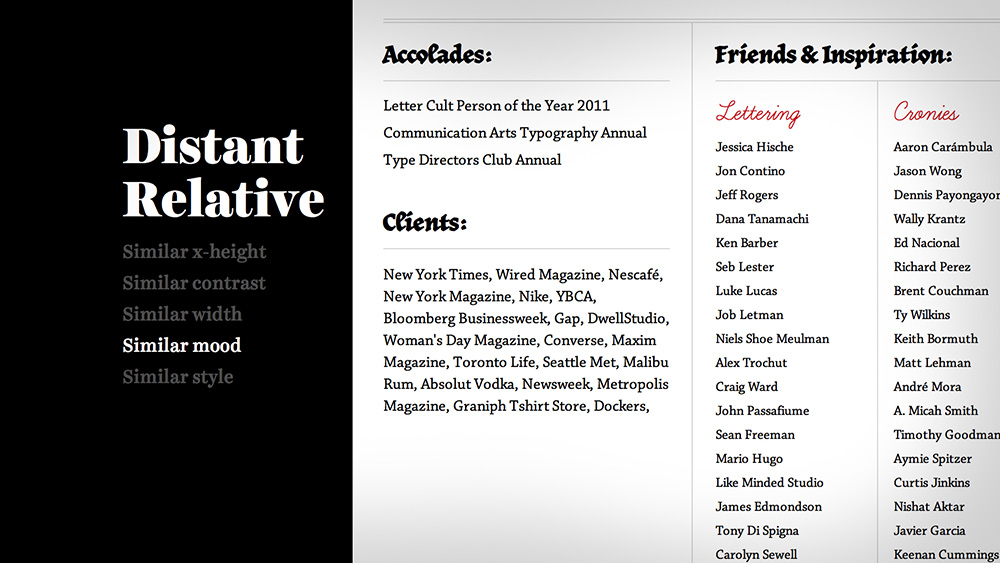

Distant Relative

- Similar x-height

- Similar contrast

- Similar width

- Similar mood

- Similar style

A sibling relationship example would be a sans-serif and serif from the same super family or a sans-serif and serif that have a very similar skeletal structure. When pairing typefaces that have a lot in common, ask yourself if the second typeface you have chosen is different enough to justify its use. Could you just get by with one typeface? Is this second typeface bringing something new to the table?

For a cousin relationship, two typefaces would have a lot in common structurally but exhibit differences that make them feel only tangentially related. Typefaces from the same type designer that are very different stylistically or typefaces created in the same era that share subtle similarities might be considered cousins. Some of the words you wrote down during your brainstorming session may come in handy now to help you figure out what your typefaces have in common.

To pair distant relatives together you have to get a little loose. Sometimes the only thing that unites a pair of typefaces is their mood or the feeling that you get when you see them. Some typefaces are like married couples that on paper seem like a terrible match but when you see them together it all makes sense.

Herb, Learning Curve, and Chaparral Pro on Erik Marinovich’s about page.

-

Don’t be afraid to experiment!

Web designers can easily test and play with many typefaces before committing to them thanks to free trials offered by foundries and web fonts services as well as tools like Typecast, which allows you to design with live fonts in the browser. Typecast is owned and operated by Monotype but includes typefaces by other foundries as well. Anyway, go forth! Have fun! Make the web a prettier and typeier place!

I know many of you went to art school and I’m assuming most of the people reading this article are designers, illustrators or others working within the world of what we reluctantly call “communication art”. When we graduated from art school, a career was promised to us. We wouldn’t spend our days covered in grape jelly, masturbating before crowds to win a spot at the Whitney Biennial—we would live normal lives, work at offices, bask in the glow of our computers. We would have stability and wouldn’t have to worry about how our “art” would pay the bills. Our parents were happy, we were happy, our fine-art friends called us sell-outs and all was right in the world.

We found our first job. After a couple years we wanted a change of pace and found a new one. Things were good. Life was easy. Mornings were spent perusing cute overload before the coffee kicked in. We designed without ever having to really deal with clients, invoicing, negotiating—all the icky businessy stuff that bums everyone out. Our left-brain atrophied.

Then one day we woke up with the itch. It became more and more powerful as we dragged ourselves to work on blizzardy days or suffered through hangovers under fluorescent lights and drop ceilings. At 7am, half awake under the weak arc of water emptying from our shower head we said to ourselves “I’m going to do it! I’m going to go freelance!” We threw on a towel and the world felt sparkly and new. We’d make our own hours! We’d sleep until noon if we wanted to! We’d no longer worry about using up all of our sick days. We’d be in control! (The freelancers reading this are without a doubt rolling their eyes at the naiveté we all once possessed). We gave notice at work and a few weeks later our dream was a reality. As time went on though, we realized this reality was not always a dream come true.

Now we were more than creatives, we were business people. If we were one of the lucky ones, we picked up enough client work to keep us from retreating, tail between our legs, to our previous lives as employees. We completely fucked ourselves over on those first few jobs but eventually cobbled together a relatively good standard contract and learned to say enough is enough after the 10th round of revisions. This is not the stuff we learned in college. If you even thought about contracts and invoices before that art school diploma hit your hand I commend your professors, but most of us were off in la la land developing identities for fictitious products, complaining about how we only had seven weeks to get that logo right.

You can learn a lot of the business end of design and illustration by trial and error and reading articles and books, but one thing that is seemingly impossible to get a grasp on is pricing. Whether you are a student, a young designer, or a seasoned pro, pricing jobs can be one of the most frustrating parts of the creative process. The cost of creative work is shrouded in mystery and very subjective. While it makes some people uncomfortable to talk about art and money together (as we all know creatives are really meant to suffer through life and die penniless), they are incredibly similar when you think about it. What is money other than dirty rectangles of pressed tree pulp? Because we all believe it has value it is valuable.

I know you’re all dying for me to get down to brass tacks and explain how to price for each and every design situation, but what follows won’t be anywhere close to a definitive guide, just some of my own opinions and words of wisdom on how to avoid screwing yourself and the rest of us over by doing too much work for too little pay. We’re in charge of assigning value to what we do. Alright, here we go!

-

Pricing hourly punishes efficiency.

So this is a pretty bold statement and like any bold blanket statement it should be taken with a grain of salt. Hourly pricing can be incredibly advantageous in certain circumstances, like when you receive that first email from a potential client and, through their thousand word introductory essay lousy with emoticons and unnecessarily capitalized words, they paint a clear picture that they are completely batshit insane. You know that there will be many rounds of revision in your future and that over the course of working together you’ll be as much a therapist as a designer. Totaling those 500 hours at whatever your hourly rate is will equal a pretty good pay day.

It’s more than just crazy people that can make hourly pricing worthwhile though—pricing any long term design project hourly can be advantageous, as long as you communicate clearly along the way what kind of hours you’re devoting to the project. If the first time your client sees your total hours is on the job-concluding invoice, a world of hurt awaits. It will be like being audited except somehow more unpleasant. Be prepared to forward them every approving email, to itemize every minute spent on the website / book / whatever.

Pricing hourly seems much easier than flat rate pricing, but because you have to give clients a ballpark full-cost price upfront (the total hours you plan to work x hourly rate), you can end up in a very tough spot if you don’t have a firm grasp on how long it takes you to do things. You’re nearing the halfway point in the project and are already over the total hours you’re contractually committed to. What does this mean? It almost never means that you’re paid double your original fee. Even if you can eek out a little extra money from the client, by the end of the project your hourly rate will look more like the one you were earning at the Blue Comet Diner at age 16.

So once you have a grip on your work flow and become more and more efficient, hourly pricing makes perfect sense, right? You know how long it will take you to do something, you price for it, everyone is happy. Unfortunately this is a half truth. Sure you’re getting paid well enough and certainly making more hourly than you probably were at your old day job, but I’ll paint a picture as to why this is a flawed pricing model: Two designers are hired to produce posters for a music festival. Both have the same hourly rate of $100 per hour (a reasonable rate for someone that’s been in the biz for a few years and has a few accolades under their belt), but one designer works much faster than the other. Both are equally talented, but one is far more efficient. At the end of the job, the designers turn in their invoices—he worked on it for a total of 18 hours and she a total of 7 hours. He is paid a respectable fee of $1800 and she $700 for producing the same result. Your rational mind says “Well, he did work more hours than her...” but part of you knows that this isn’t completely fair, and that part is correct. This becomes epically clear when working for big name clients.

Here’s another scenario: You’re hired to do a monogram for a giant international company. They’ll want to use this monogram on everything from price tags to billboards to TV spots and they want to use it forever (in perpetuity until the sun explodes). They have a pretty clear idea of what they want and you know that it will take about 10 hours total with the initial exploration, back and forth revisions, and finalizing. Even if your hourly rate is $250 / hour (a pretty high rate), the total you’re earning for that logo is $2,500. If you think that is a good price for a professional designer to earn crafting what is essentially a logo for a huge company, you are mistaken. So if you aren’t pricing hourly, how DO you price?

Licensing and Rights-Management

So while pricing hourly has its disadvantages, it’s a good place to start. Most designers take into account the hours they’ll put into a project when coming up with a price, but the seasoned professionals use it as part of the way they quote a project, and not as the only defining factor. Once you feel comfortable with your hourly rate and can somewhat accurately predict how long it will take you to do something, there are a few other things to consider that will boost your prices and turn this design hobby of yours into an actual sustainable career.

As a designer, when you hear the term “rights-management” it takes you back to your intern days doing photo research, trying to find non-awful royalty-free images after your boss told you all the rights-managed photos were way too expensive. How does rights-management apply to a designer or illustrator? Photographers aren’t the only ones able to manage the rights of their work. You inherently own the rights to anything you create, this is why it’s incredibly important to read every contract for every job. Often times clients want more rights than what they are willing to pay for—the biggest red flag word being “work for hire”. This means that the client owns all the rights to anything you create for them. They essentially, legally, become the author of your work.

As a graphic designer, work for hire is a bit more acceptable in many situations since you’re not authoring new content as much as creating a beautiful context for other people’s content (speaking specifically about any sort of layout design). Where rights management usually comes into play is in the context of identity work, and this is why logos are priced the way they are. It’s understood that the clients will need the rights to the mark you create so that they can trademark it and use it on unlimited applications, so when pricing for a logo you should take that into account. In addition to a fair hourly rate, clients pay for the rights to use that logo in an unlimited capacity.

Aside from giving away all the rights to your work for an additional (hopefully ginormous) fee, you can give them away for limited periods of time or for limited applications by licensing work to clients. There are fewer ways to do this as a graphic designer, but licensing is an incredibly (incredibly!) important part of being an illustrator or letterer. Of the couple hundred client projects I’ve done over the past few years, very few of them have required a full buyout of all rights, and the ones that have required them paid my rent for the better part of a year. Here are some factors that go into pricing a job based on licensing:

- How long does the client want to license the artwork for?One month? One year? Two years? Five years? In perpetuity?

- In what context is the artwork going to be used?Do they have the rights to use it on anything? In print only? Web only? Broadcast? Tattooed on their faces?

- If the job is reprinted, will there be an additional fee for a reprint?

- Do they want an unlimited license or do they need to own the rights?

- Are these rights transferrable if the company is sold?

- What kind of company is it?Is it for a Mom-and-Pop business, a multi-billion dollar corporation or something in between?

By now your head must be spinning. This is some complicated stuff right? Maybe, but this is how you can actually make a living doing illustration and design and maybe even eventually quit your but-they-give-me-health-insurance barista job. What follows is a fictional pricing example to show how powerful licensing can be. I’m going to write it in the context of lettering, which is priced essentially the same as illustration. Graphic designers should still pay attention though, because when I talk about buyout pricing, that’s essentially what you’re going to be thinking about when pricing logos. My price points will be higher than what a fresh faced n00b can probably charge, but should at least illustrate how much of an impact licensing can have on the cost of artwork.

-

The Correspondence

Dear Ms. Hische,

I’m an art director at Awesome Agency Inc, working on a campaign for an international clothing brand (on par with the gap) and am writing to gauge your interest in creating artwork for us. We need one five-word phrase illustrated in a script style. The artwork should be highly illustrative, attached are some examples of work you and others have done that are in the ballpark of what we want for the campaign. If this sounds appealing to you, please send us a quote by end of day tomorrow so that we can present your work, along with a few others we are gathering quotes from, to the client. Thanks so much and look forward to working with you!

Sincerely,

Arthur Director

They didn’t give me much to go on here aside from the actual work I’m creating. It sounds like a cool job, but I’m going to need to do some investigating before giving a proper quote. The biggest young designer mistake here would be to quote a flat fee without finding out what kind of usage rights they want.

Thanks so much for thinking of me Arthur! I’ll put together a quote this afternoon. Do you want me to price for every usage scenario or do you have some specific uses in mind?

All the best,

Jessica

Usually here they’d write back with some very very specific uses in mind which makes it a bit easier to quote, but sometimes you’ll get a letter that looks something like this:

Hi Jessica,

Great to hear back from you! We’re still in the exploratory stages of the project, so we can’t give specific usage situations yet. Please quote for creation of artwork for presentation only and for a few ballpark usages.

Arthur

-

What We Know

- This is for a big international clothing company.

- They are gathering prices from a few different people.They’ll present several artists to the client who will chose based on style or lowest price depending on what the client’s priority is.

- They want a price for presentation only.This means you create the artwork and they only have the right to show it around in-house and to the client, NOT to use it in any way for their campaign.

- They want a number of usage scenarios.This is on top of that initial creation / presentation fee.

-

Pricing for Presentation

If you’ve done any editorial illustration work (magazines and newspapers), you know that the rates are pretty standard across the board: $250-$500 for a spot illustration, $500-$750 for a half page, $1000-$1500 for a full page, $2000-$3000 for a full spread, $1500-$3500 for a cover. These are all pretty normal prices and there are of course magazines that pay higher or lower. I tend to start with these prices in mind when thinking about pricing for “Presentation Only”.

They want a five word phrase that is highly illustrative, which equates to “a full page illustration” or so. Because this is for advertising and not editorial, adjust your rates depending on the client. This is for a big company, so my presentation only fee might be somewhere around the $5000-$7000 mark depending on how complicated what they’re after actually is. If this was for a smaller company, the presentation only fee might be closer to $2500 or $3500.

-

Sample Usage Scenarios

If a client doesn’t tell you specifically what usage rights they need, you should make sure there is a good range represented. In this situation, I’m definitely going to price based on the length of time they need it, plus some general examples of what context the artwork will be used in. When you send your quote, it should be broken down as clearly as possible so there is no confusion as to what the clients are paying for in each stage of rights licensing. This would be the quote I would send back:

Hi Arthur,

Below are a few sample quotes for the project. As I did not have much info about what usage rights you needed, we would need to talk specifically about anything not mentioned below once the client has a clearer picture of what they need.

-

Presentation Only: $7000

2-3 initial pencil sketches shown, one chosen to be created as final art. After final artwork is presented, the client may request up to two rounds of minor revision. Additional revisions after this point will be billed at $250/hr. If the client chooses to not move forward after pencils are presented, a kill fee of $3500 will be paid for completion of sketches. If artwork is completed to final, the full fee will be paid.

-

Usage Scenario 1: +$5000

The client may use the artwork in magazine and newspaper ads (domestic and international) for a period of 1 year.

-

Usage Scenario 2: +$7500

The client may use the artwork in all print media (domestic and international) including but not limited to magazines, newspapers, point-of-purchase displays, posters, and billboards for a period of 1 year.

-

Usage Scenario 3: +$10,000

The client may use the artwork in all print and online media for a period of 1 year.

-

Usage Scenario 4: +$14,000

The client may use the artwork in all print media, all online media, and broadcast media for a period of 1 year.

-

Buyout: +$25,000

The client may use the artwork in all media including print, online, and broadcast in perpetuity.

Thanks so much for thinking of me for the project, let me know how these numbers go over and if you need any clarification about the different usage points.

All the best

J

So this is a pretty basic breakdown, but it gives the agency/client a lot of price points to consider. If I wanted to break it down even further, I would price based on 2 year and 5 year use and give different prices for U.S. only, North America only, etc. Most importantly, note that all of the usage scenarios are on top of our original presentation only / artwork creation price. The prices are not cumulative in this example quote, so each +$ is only added to the presentation fee. The top price in this scenario is $32,000 (I saw there was some confusion in comments so thought I’d clarify). These prices might seem completely outrageous to you, but they’re actually pretty reasonable when we take into effect who the client is and what kind of rights they’ll probably need. If you’re an up-and-comer, your prices might be a bit lower but the percentage markup should remain about the same. Imagine if we had priced this hourly!

-

How do you know if you priced right?

If the client writes back immediately and says “These numbers look great! We’ll send along a contract for you to go over in a few days!” It probably means your prices are too low. If they write back and try to negotiate you down a little bit, you were probably pretty spot on, and if they write back and say that this is well beyond their budget, you get to decide whether or not you want to figure out a way to work within their budget or whether you want to walk away and take one for the team. When you’re offered a very low budget by a very huge client, you can always feel good about turning it down knowing that you are helping to raise the standards of pricing for others.

-

Why doesn’t anyone ever talk about pricing?

There are a lot of reasons why designers and illustrators are reluctant to talk about pricing, the most obvious being that no one wants to shout their annual income to the masses. Once you start giving away your general prices, it’s not incredibly difficult to add things up and figure out a ballpark of what an individual or company makes in a year. A personal note: don’t assume that the pricing structure above means that I’m swimming in a pile of money. My half-retired dentist father still makes more than I do. The fake job I used as an example above is an advertising job, and I used it as an example because pricing for advertising is one of the darkest arts of all. There are wild differences in pricing from presentation to buyout, and a ton of factors that affect the price. It’s great to surround yourself with friends or more experienced designers that can help you price a job. You can always consult The GAG’s Ethical Guide for Pricing, but definitely use it for ballparking more than definitive numbers.

-

The Pricing Domino Effect

It’s incredibly important for even young designers to always quote respectable prices. It can be very tempting to create artwork for a “cool” company for very little pay and the promise of insane exposure / an incredible portfolio piece. Every successful designer and illustrator has at one point succumbed to the siren song of the “cool” industries (there are a few “cool” companies that don’t try to take advantage of designers but they are the exception and not the norm). When you are starting your career as a freelancer, it will be incredibly tempting to take on any work that comes along, no matter how unfairly companies are trying to compensate you. Remember that you are talented and that your talent has value and that ultimately it is up to you to determine how much people value your talent. By helping to keep pricing standards high, you not only help yourself by avoiding the title of “The Poor Man’s Marian Bantjes” (essentially the creative equivalent of a knock-off handbag), you also help every other young designer struggling to get paid out there, and help every designer that came before you to continue making a living doing what they love.

A footnote for the haters:

For whatever reason, whenever anyone writes an article like this—asking designers to raise the standards for themselves and others, calling out companies for unfair pay or empty promises—there are always a few anonymous contrarians that berate the author for preaching from an ivory tower, not understanding what the masses are actually going through. I have been lucky enough to have success in my career, and I want to use the knowledge I’ve gained to help others have success. Why anyone would complain when someone is advocating for better wages, I do not know, but it always happens.

As I’ve watched my flowchart get reposted around the internet a bit, there is a topic that is always brought up in comments that I didn’t address on the chart itself: internships. I purposefully avoided talking about them on the chart, just as I avoided diving into great detail about non-profit work—because both are pretty complex matters. When it comes to non-profit work, I know several designers that make their entire living working at or doing freelance for non-profits. On the chart, I wanted to get the point across that most non-profits are legitimate businesses and that while they aren’t declaring profit at the end of the year, they still have expected operating costs and your design work should not necessarily be left out of the mix. Anyway, I’m already off on a tangent, let’s get back to the issue at hand.

When I was in college, my university wouldn’t give you academic credit for an unpaid internship. Local design studios knew this, and knew that if they wanted an intern from Tyler School of Art, they would have to fork over some cash (albeit very little cash). It worked out great. Of the three internships I had in college, all were paid. That doesn’t mean I was raking it in, but I was able to change my humble diet of ramen to…pasta.

There is (and has always been) a giant trend to compensate interns in “experience” alone. It’s one thing for a 18-year-old that has never opened Photoshop to walk into a tiny design studio and expect little or no compensation, but the more I talk to young designers struggling to get work, the more I see people in their early and mid-twenties (most with bachelor and graduate degrees) having to settle for unpaid internships in their quest to find a real job. These are people with real skills and they are being taken advantage of. Everyone knows that you won’t get rich from an internship, but companies (even tiny ones) can afford to pay you something for your time, even if what you’re being paid amounts to little more than minimum wage in a city like New York. The big argument you’ll hear against paying interns is that you are learning a lot from the company or designer you’re working for and that their time is so valuable that they are working at a loss to educate you. This is complete bullshit. Well, maybe not complete bullshit but definitely a hearty serving of it.